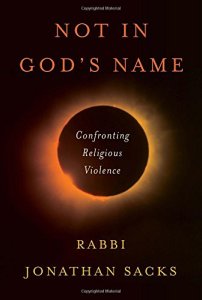

In this first interview, conducted by First Things Senior Editor Mark Bauerlein, Jonathan Sacks talks about themes attended to in his latest book, Not In God’s Name: Confronting Religious Violence. They discuss René Girard’s mimetic theory, the sibling rivalry that characterises the relationships between Abraham’s most enduring children – Jews, Christians, and Muslims – and the infinite depths and breadths of the divine love for them all.

The second interview is conducted by Walter Russell Mead, and then opens up to many questions from the floor. Here, Sacks explores the roots of religious extremism, the roots and natures of violence, different ways of reading those religious texts common to Abraham’s kids, secular nationalisms, and more:

And, two excerpts from the book:

And, two excerpts from the book:

When religion turns men into murderers, God weeps.

So the book of Genesis tells us. Having made human beings in his image, God sees the first man and woman disobey the first command, and the first human child commit the first murder. Within a short space of time ‘the world was filled with violence’. God ‘saw how great the wickedness of the human race had become on the earth’. We then read one of the most searing sentences in religious literature. ‘God regretted that he had made man on the earth, and his heart was filled with pain’ (Gen. 6:6).

Too often in the history of religion, people have killed in the name of the God of life, waged war in the name of the God of peace, hated in the name of the God of love and practised cruelty in the name of the God of compassion. When this happens, God speaks, sometimes in a still, small voice almost inaudible beneath the clamour of those claiming to speak on his behalf. What he says at such times is: Not in My Name.

Religion in the form of polytheism entered the world as the vindication of power. Not only was there no separation of church and state; religion was the transcendental justification of the state. Why was there hierarchy on earth? Because there was hierarchy in heaven. Just as the sun ruled the sky, so the pharaoh, king or emperor ruled the land. When some oppressed others, the few ruled the many, and whole populations were turned into slaves, this was – so it was said – to defend the sacred order written into the fabric of reality itself. Without it, there would be chaos. Polytheism was the cosmological vindication of the hierarchical society. Its monumental buildings, the ziggurats of Babylon and pyramids of Egypt, broad at the base, narrow at the top, were hierarchy’s visible symbols. Religion was the robe of sanctity worn to mask the naked pursuit of power.

It was against this background that Abrahamic monotheism emerged as a sustained protest. Not all at once but ultimately it made extraordinary claims. It said that every human being, regardless of colour, culture, class or creed, was in the image and likeness of God. The supreme Power intervened in history to liberate the supremely powerless. A society is judged by the way it treats its weakest and most vulnerable members. Life is sacred. Murder is both a crime and a sin. Between people there should be a covenantal bond of righteousness and justice, mercy and compassion, forgiveness and love. Though in its early books the Hebrew Bible commanded war, within centuries its prophets, Isaiah and Micah, became the first voices to speak of peace as an ideal. A day would come, they said, when the peoples of the earth would turn their swords into ploughshares, their spears into pruning hooks, and wage war no more. According to the Hebrew Bible, Abrahamic monotheism entered the world as a rejection of imperialism and the use of force to make some men masters and others slaves.

Abraham himself, the man revered by 2.4 billion Christians, 1.6 billion Muslims and 13 million Jews, ruled no empire, commanded no army, conquered no territory, performed no miracles and delivered no prophecies. Though he lived differently from his neighbours, he fought for them and prayed for them in some of the most audacious language ever uttered by a human to God – ‘Shall the Judge of all the earth not do justice?’ (Gen. 18:25) He sought to be true to his faith and a blessing to others regardless of their faith.

That idea, ignored for many of the intervening centuries, remains the simplest definition of the Abrahamic faith. It is not our task to conquer or convert the world or enforce uniformity of belief. It is our task to be a blessing to the world. The use of religion for political ends is not righteousness but idolatry. It was Machiavelli, not Moses or Mohammed, who said it is better to be feared than to be loved: the creed of the terrorist and the suicide bomber. It was Nietzsche, the man who first wrote the words ‘God is dead’, whose ethic was the will to power.

To invoke God to justify violence against the innocent is not an act of sanctity but of sacrilege. It is a kind of blasphemy. It is to take God’s name in vain.

And …

Terror is the epitome of idolatry. Its language is force, its principle to kill those with whom you disagree. That is the oldest and most primitive form of conflict resolution. It is the way of Cain. If anything is evil, terror is. In suicide bombings and other terrorist attacks, the victims are chosen at random, arbitrarily and indiscriminately. Terrorists, writes Michael Walzer, ‘are like killers on a rampage, except that their rampage is not just expressive of rage or madness; the rage is purposeful and programmatic. It aims at a general vulnerability: Kill these people in order to terrify those.’

The victims of terror are not only the dead and injured, but the very values on which a free society is built: trust, security, civil liberty, tolerance, the willingness of countries to open their doors to asylum seekers, the gracious safety of public places. Religiously motivated terror desecrates and defames religion itself. It is sacrilege against God and the life he endowed with his image. Islam, like Judaism, counts a single life as a universe. Suicide and murder are forbidden in the Abrahamic faiths. Judaism, Christianity and Islam all know the phenomenon of martyrdom – but martyrdom means being willing to die for your faith. It does not mean being willing to kill for your faith.

Terror is not a justifiable means to an acceptable end, because it does not end. Terrorists eventually turn against their own people. Walzer again: ‘The terrorists aim to rule, and murder is their method. They have their own internal police, death squads, disappearances. They begin by killing or intimidating those comrades who stand in their way, and they proceed to do the same, if they can, among the people they claim to represent. If terrorists are successful, they rule tyrannically, and their people bear, without consent, the costs of the terrorists’ rule.’ There is no route from terror to a free society.

Nor is it the cry of despair of the weak. The weak have different weapons. They know that justice is on their side. That is why the prophets used not weapons but words. It is why Gandhi and Martin Luther King preferred non-violent civil disobedience, knowing that it spoke to the world’s conscience, not its fears. True need never needs terror to make its voice heard.

The deliberate targeting of the innocent is an evil means to an evil end, to achieve a solution that does violence to the humanity and integrity of those we oppose. To give religious justification to it is to commit sacrilege against the God of Abraham, who is the God of life. Altruistic evil is still evil, and not all the piety in the world can purify it. Abraham’s God is the power that rescues the powerless, the God of glory who turns the radiance of his face to those without worldly glory: the poor, the destitute, the lonely, the marginal, the outsiders of the world. God hears the cry of the unheard, and so, if we follow him, do we.

Now is the time for Jews, Christians and Muslims to say what they failed to say in the past: We are all children of Abraham. And whether we are Isaac or Ishmael, Jacob or Esau, Leah or Rachel, Joseph or his brothers, we are precious in the sight of God. We are blessed. And to be blessed, no one has to be cursed. God’s love does not work that way.

Today God is calling us, Jew, Christian and Muslim, to let go of hate and the preaching of hate, and live at last as brothers and sisters, true to our faith and a blessing to others regardless of their faith, honouring God’s name by honouring his image, humankind.

I entirely agree with what Jonathan Sacks says.

The problem is that the bible is as full of curses as blessings,(e.g. Deut. 28) and the Jews were commanded to wipe out the Amalekites etc. . . in God’s name.

That is one of the dilemmas I struggle with as I read my Bible.

LikeLike