A guest post by Joel Daniels.

1) Williams exaggerates the importance of maintaining unsettledness, preventing resting, etc.

Williams shares with Donald MacKinnon a sense of the moral priority of tragedy, and one gets the sense that he sees a straight line from closure to murder. At the risk of being too flip about it, the road to genocide is paved with good intentions. Efficient systems, set up by well-meaning people, to accomplish the greatest ends, eventually justify the most atrocious horror: it is fitting that one man should die for the people. Or the shaken revolutionary Shigalyov in Dostoevsky’s Demons, who has written out the plan for the revolution, reporting that, “Starting from unlimited freedom, I conclude with unlimited despotism. I will add, however, that apart from my solution to the social formula, there is no other.” Efficient theoretical systems (economic, political, philosophical, theological) produce victims, with the crucified Christ, one without sin, being the pure example of this fact – though the history of the last century provides ample examples by itself. I think that this really is the overarching concern of Williams’ theology.

Part of this may simply be disposition: there’s a really revealing line in WWA where he’s comparing Balthasar and Rahner, and he writes, “for Balthasar, dialogue with ‘the world’ is so much more complex a matter than it sometimes seems to be for Rahner; because [for Balthasar] the world is not a world of well-meaning agnostics but of totalitarian nightmares, of nuclear arsenals, labor camps and torture chambers” (100). If you look at the world and see harmony, you end up in one theological place; if you see torture chambers, you end up in another. I think the relentless self-criticism comes from having the second perspective as his default.

The downside of this is what Chris described; Mike Higton (in Difficult Gospel) puts it this way: “But I suspect that the tenor or atmosphere of his [Williams’] writing is too unrelentingly agonized…” Perhaps so; I remember reading that MacKinnon couldn’t order lunch without severe moral anguish.

2) For Williams, the logical outcome of good theology is the silence of frustration, not of adoration.

What prevents simple frustration supplanting the possibility of positive worship is the strong element of Anglican orthopraxis at work: while it may be the case that the Cross reveals that there is nothing we can securely know or think (frustration), the practice of worship (adoration) takes priority over the practice of theology. It would be interesting to know whether Williams would adopt Pseudo-Dionysius’ use of “hymn” as a theological category, along the lines of the “celebratory” mode of theological work he describes. If so, perhaps we could say that good theology culminates not in silence, but in the singing of the liturgy. It’s as if the Eucharistic service provides a kind of foundation from which we can work and to which we can return: our Eucharistic celebration may not be perfect; it is certainly interpreted by fallible human beings; and entails its own risks (clericalism, among many others). Nonetheless, we can identify the effect of the Eucharist over the course of history to complicate any easy answers, by returning us to the broken body of Christ.

3) Similarly, the effect Williams has is to make it too difficult to talk about God; the end result is paralysis or restlessness.

It’s not so much that we shouldn’t make attempts to talk about God (paralysis), as that we have to realize that no attempt is ever final: it’s dialectic all the way down. Is this eternal restlessness? In a sense, I think it probably is. But I hope that it’s the restlessness of two lovers’ delight in each other, not the restlessness of dissatisfaction; the kind of restlessness that is the way that the meaning of a great text (for example) is never exhausted, but always there to be plumbed for meaning, new circumstances bringing out existing aspects of the same work in a different light.Further, some attempts at talking about God are better than others, and one of the benefits of the tradition is a head start, so to speak, in identifying which ones are going to be liberating and fecund, and which will lead to dead ends, inconsistencies with the Eucharist, or something worse.

4) Williams makes anti-programmatic thinking programmatic.

I can understand a concern about a conception of theology that sees as its primary objective the destabilization of every affirmative statement about God – especially when that destabilization is being done by a professional class that isn’t explicitly or especially in relationship with a worshipping community. There is a difference between a smirking hermeneutic of suspicion and a pious refusal of idolatry, but they may look quite similar on the page. Further, an affinity for disruption can become its own security blanket.

At the very least, we can see that Williams is aware of that: I frequently return to the sermon “The Dark Night,” with its first paragraph “If I am a ‘conservative’ my circular path will be one of conventional sacramental observance… If I am a ‘radical’ my God will be the disturber of the social order… Both of these pictures as they stand are delusional.” Both of them use God to accomplish some other ends. I think he does a pretty good job at this, keeping his own perspective under interrogation also.

I wonder is RW ever read much of Luther, and his ‘Theology of the Cross’? “theologia gloriae” is always problematic in High Church theology!

LikeLike

*if

LikeLike

This is such a helpful post. Thanks! I love the contrast between how Balthasar and Rahner see the world and the question of the tragic. It seems to me that the contrast would be good as the starting point for a theological and anthropological discussion re things like principalities and powers and how they function regardless of good intentions, and how the logic of desire works (pace Girard, Augustine, eg) and whether this leads one to a more Balthasarian perspective and whether or not this is necessarily a tragic one in tradition of MacKinnon (denied however by Bentley Hart)

LikeLike

What do you reckon Andre? Or are you busy buying lunch?

LikeLike

Some of the theological shorthand here is a bit beyond me, but section three offers (for me) the most comprehensible view on this ongoing discussion about Williams: we never fully understand the person we’re married to; in fact, it’s entirely possible that after being married for many years to wake up and ask ‘Who on earth is this person sleeping in my bed?’ So too with God.

LikeLike

Too much God talk?

LikeLike

I remember watching a Compass (ABC-TV) program a few months ago about an Irish priest/missionary in Indonesia for many years who was asked by his superior “why aren’t you converting these people?” The priest replied, “My job is to love them, not push my agenda. I wouldn’t be loving them if I did that”. He happily mixed with his Muslim brothers. As well as tending his own flock of Catholic faithful. I liked that.

LikeLike

That is certainly not the pattern of the early Church, not a Paul, Peter or John, etc. Even 1 Cor. 13: 6 says: “Love” (verse) 4…”does not rejoice in iniquity (unrighteousness), but rejoices in the truth.” (Note the article) The core of the Judeo-Christian faith is the revelation of God, in the doctrine of God, which will always be seen as our Lord said…”when the true worshipers will worship the Father in ‘spirit and truth’, for the Father seeks such people to be his worshipers.” (John 4: 23) And as John 4:21-22, “salvation is of/from the Jews”, and not from the Samaritans “this mountain”, or any other place of people besides the Jews (the Incarnation and Covenant/covenants of God).

LikeLike

And yet it was the Samaritan who truly loved his neighbour…..

LikeLike

Indeed, in the parable!

LikeLike

I’m not expert on RW, but this is a very fine piece. Well done, Joel (if you’re reading), and thanks Jason for bringing it to us.

LikeLike

I agree with WTM: this is a fine piece, Joel. You certainly articulate well what it is that I’m sometimes afraid Williams is doing. My favorite bit is probably the distinction you draw between the restlessness of delight and the restlessness of dissatisfaction. Thank you again for this.

LikeLike

Andre, is buying lunch really that difficult? :-)

LikeLike

Thanks for the conversation about this; I’ve found the back and forth incredibly helpful.

One area maybe you guys can help me on: on the one hand, RW says things like, “The world has no discernible meaning or pattern” (ROD, 190); “God alone is the end of desire, and that entails that there is no finality, no ‘closure’, no settled or intrinsic meaning in the world we inhabit” (1989 Lit & Theo piece), and so forth. On the other, he seems pretty certain that there is a real, accessible moral order (one of MacKinnon’s emphases, too – “Morality is not a matter of arbitrary choice; it is in some sense expressive, at the level of human action, of the order of the world” [Problem of Metaphysics, 38]).

How do those two things fit together? What am I missing? Does this have something to do with natural law?

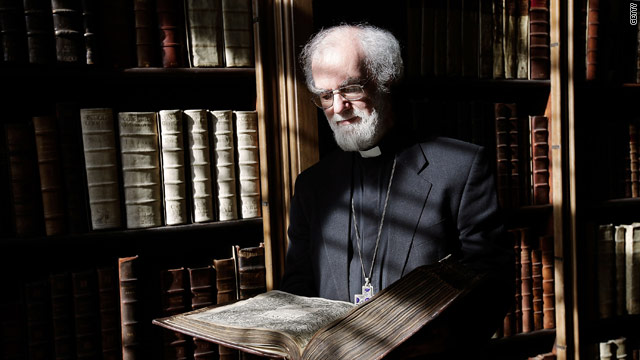

Also – what is he reading in that picture at the top of the page?

LikeLike

For me anyway, RW’s “theology” is just not “Incarnational” fully, or really Christological, nor certainly theocentric! But hey, I am an old Augustinian, and an Anglican who is foremost Reformational (always Luther) and too Reformed (Calvin). And note even for Barth there is no “natural” theology! Yeah there are still a few of us in this certain historical place! ;)

LikeLike

Fr. Robert – Rowan has an extensive discussion in ‘The Wound of Knowledge’ on Luther.

LikeLike

Brett: Yes, I have seen some of this, it simply seems like a disconnect by RW to me.

LikeLike

The real Luther theologically and even in mystical lines, simply cannot be understood without his doctrine and Theology of the Cross! And here too, comes into play the reality of “theologia gloriae” for Luther. As theology for Luther was always pastoral, see btw, Zachman’s book: The Assurance of Faith, Conscience in the Theology of Martin Luther and John Calvin. (Part One is Luther)

LikeLike

Here is a piece from my own blog…

The ‘theologia gloriae’ or theology of glory, was Luther’s term for the rationalistic theology of the scholastics. They tended to talk about God in terms of his glorious attributes rather than in terms of God’s self-revelation in the cross and suffering. This appears to be very problematic today also. But we must have the ‘theologia crucis’..the theology of the cross in the central place of the Gospel!

This is Luther’s radical position of just what the “theologia crucis” is contra to the “theologia gloriae”. Of course God has His attributes of glory, but in light of the Cross and the kenosis of Christ, we are always drawn to Christ of Calvary!

LikeLike

A very thoughtful post, thank you. I would also suggest that for Rowan, as ABC, continuing dialogue = continuing communion, in some form or other. As he writes elsewhere, the door must be kept open for further conversation.

LikeLike