In a previous post in this series, I drew attention to a study leave project undertaken by Diane Gilliam-Weeks. I suspect that Diane is right (especially so long as the practices she is encouraging are built in to the formation process rather than treated as an isolated subject), but the issue painted thus threatens to individualise both problem and solution. For the high rate of clergy burnout reflects not only sick persons but also sick institutions; churches, as PT Forsyth put it,

In a previous post in this series, I drew attention to a study leave project undertaken by Diane Gilliam-Weeks. I suspect that Diane is right (especially so long as the practices she is encouraging are built in to the formation process rather than treated as an isolated subject), but the issue painted thus threatens to individualise both problem and solution. For the high rate of clergy burnout reflects not only sick persons but also sick institutions; churches, as PT Forsyth put it,

‘that seem to live in an atmosphere of affable bustle, where all is heart and nothing is soul, where men decay and worship dies. There is an activity which is an index of more vigour than faith, more haste than speed, more work than power. It is sometimes more inspired by the business passion of efficiency than the Christian passion of fidelity or adoration. Its aim is to make the concern go rather than to compass the Righteousness of God. We want to advance faster than faith can, faster than is compatible with the moral genius of the Cross, and the law of its permanent progress. We occupy more than we can hold. If we take in new ground we have to resort to such devices to accomplish it that the tone of religion suffers and the love or care for Christian truth. And the preacher, as he is often the chief of sinners in this respect, is also the chief of sufferers. And so we may lose more in spiritual quality than we gain in Church extension. In God’s name we may thwart God’s will. Faith, ceasing to be communion, becomes mere occupation, and the Church a scene of beneficent bustle, from which the Spirit flees. Religious progress outruns moral, and thus it ceases to be spiritual in the Christian sense, in any but a vague pious sense’. – The Preaching of Jesus and the Gospel of Christ, 119.

Rick Floyd, too, has recently reminded us, rightly in my view, that ‘much [though certainly not all: beware the scapegoat!] of what passes for burnout is merely the symptoms of an untenable arrangement’. He continues: ‘Clergy have both sold and been sold a bill of goods that they can neither deliver to the church nor receive delivery from the church. And since the mainline churches (at least in America) are an institution experiencing a half-century of precipitous institutional decline the opportunities for failure and disappointment are almost limitless. The measures of success the world values will most likely elude the minister. Indeed, a “successful minister” is an anomaly in a faith with a cross at its center. It takes a hearty sense of Christian vocation to handle this. For many the very nature of the task will get you quickly to burnout. And, as the models for ministry has become increasingly professionalized, more and more ministers will find themselves wondering what they have got themselves into. The prescriptions for burnout typically ignore this fundamental disconnect between Christian vocation and cultural expectation. They only address the symptoms … So clergy burnout seems to me to be largely about the identity crisis of the mainline church, and the vocational crisis of its ministers. And a realistic assessment of the situation from a worldly point of view offers little to be hopeful about’.

There are, of course, other things that might be profitably explored in a series of posts like this, such as how a theology of creation, of vocation (as Rick highlights), and of Sabbath might inform the habits and identity of ministers of Word and Sacrament and of the communities of the baptised they serve with. But I want to suggest a different tact here, and it’s one motivated by what I observe as a distinct lack of christology (and its anthropological and ecclesiological implications) in the conversations that typically take place whenever discussions on clergy welfare arise. I am here guided by those insightful words from Karl Barth: ‘An abstract doctrine of the work of Christ will always tend secretly in a direction where some kind of Arianism or Pelagianism lies in wait’ (CD IV/1, 128).

We must not attempt to veil or bury the issues and pains that attend pastoral ministry by hiding behind theological jargon. Rather, we must, in fact, to do the opposite – to expose these issues and pains. And the Christian theologian will want to undertake such exposure in light of the ministry of God in Jesus Christ, and that in order to, among other things, see if there are what Lorine Niedecker calls ‘atmosnoric pressure[s]’ at work. My conviction is that there is much to be gained in thinking more deeply through some of the implications of what it means when the Church claims that to follow Jesus’ cruciform example by suffering with those who suffer, and working to relieve and eliminate suffering, carries one into the place of God’s own suffering in the world. While I am passionate about the urgency of promoting and practicing better clergy ‘wellness’, anyone who has drunk from 2 Corinthians (and other places) will know that there remains something inherently fundamental in the very nature of Christian ministry itself that will not and cannot and must not seek insulation from the cruciform suffering that attends our witness to the God of the cross and which constitutes the ethical dimension of the theology of the cross found throughout the NT and in the Christian tradition. [I have touched on this elsewhere]. The living Christ remains the crucified one, and cruciformity means Spirit-enabled conformity to, and participation in, the life of the crucified and resurrected Christ. It is the ministry of the living Christ, who re-shapes all relationships and responsibilities to express the self-giving, and so life-giving, love of God that was manifest in the action of the cross. Although cruciformity often (and perhaps always) includes suffering, at its heart cruciformity is about faithfulness and love. Cruciformity, moreover, is concerned with what a friend of mine calls ‘kenotic, and not self-abnegating love’, a love for God, for others, and for oneself as a child of God and member of God’s community whether proleptically or ‘already’. What I mean is that while there is a suffering which comes from sin, hardness of heart, selfishness, hatred and greed, etc. – i.e., from a refusal to live in the reality of our forgiveness and to embrace the means of grace given us – there is also a suffering which comes in the cause of the Gospel itself (2 Cor 4.7–15; 6.4–10; Isa 50.4–11). This includes, but is not limited to, the suffering that arises in seeing people’s hearts harden to the Gospel. Such is the privilege of service: ‘Love bears all things, believes all things, hopes all things, endures all things’ (1 Cor 13.7). And at the same time faith actually grows under the pressures (Acts 5.41; Jn 15.18–27). Barth may have been thinking along these lines when he penned these words:

‘For when man stands in the service of God, he must be able sometimes, and perhaps for long periods, to be still, to wait, to keep silence, to suffer and therefore to be without the other kind of capacity … The power which comes from Him is the capacity to be high or low, rich or poor, wise or foolish. It is the capacity for success or failure, for moving with the current or against it, for standing in the ranks or for solitariness. For some it will be almost always be only the one, for others only the other, but usually it will be both for all of us in rapid alternation … Either way, it is grace, being for each of us exactly that which God causes to be allotted to us’. (Karl Barth, Church Dogmatics 3/4 (Edinburgh: T&T Clark, 1961), 396, 397)

Uncle Karl also knew that the ministry of the gospel is also a cause of constant joy, not because suffering in and of itself is enjoyable but because it involves at its heart a participation in the life of the God of joy. So, he wrote: ‘The real test of our joy of life as a commanded and therefore a true and good joy is that we do not evade the shadow of the cross of Jesus Christ and are not unwilling to be genuinely joyful even as we bear the sorrows laid upon us’. (Barth, CD 3/4, 396, 397).

◊◊◊

Other posts in this series:

- On the cost and grace of parish ministry – Part I

- On the cost and grace of parish ministry – Part II

- On the cost and grace of parish ministry – Part III

- On the cost and grace of parish ministry – Part IV

- On the cost and grace of parish ministry – Part V

- On the cost and grace of parish ministry – Part VII

- On the cost and grace of parish ministry – Part VIII

- On the cost and grace of parish ministry – Part IX

- On the cost and grace of parish ministry – Part X

- On the cost and grace of parish ministry – Part XI

- On the cost and grace of parish ministry – Part XII

- On the cost and grace of parish ministry – Part XIII

- On the cost and grace of parish ministry – Part XIV

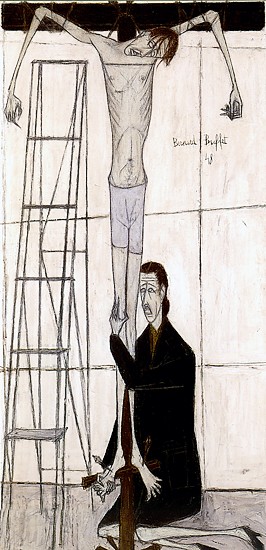

Who is the artist behind the image you have used in this post?

LikeLike

Bernard Buffet.

LikeLike

Jason,

As one who is preparing for ministerial training I have found it difficult to balance in my thinking the kenoticism you mention with what I take to be necessary attention to ‘wellness’. Few of us are ignorant of the suffering and challenges of pastoral ministry and indeed life itself, nor would I want to promote an idolization of family and the pursuit of happiness as the telos of Christian living, but I have been somewhat concerned at the ascetic tone of some comments made in response to this series. Surely we cannot afford some ‘gnostic’ view of ministry that mistakes the via crucis with a self-legitimizing view of our own pain? So, I find your reflection on cruciformity helpful because it seems to me you do not wish to dichotimize wellness and participation in “the cruciform suffering that attends our witness to the God of the cross.”

LikeLike