The logic of hell is nothing other than the logic of human free will, in so far as this is identical with freedom of choice. The theological argument runs as follows: ‘God whose being is love preserves our human freedom, for freedom is the condition of love. Although God’s love goes, and has gone, to the uttermost, plumbing the depth of hell, the possibility remains for each human being of a final rejection of God, and so of eternal life’. Does God’s love preserve our free will, or does it free our enslaved will which has become unfree though the power of sin? Does God love free men and women, or does he seek the men and women who have become lost. It is apparently not Augustine who is the father of Anglo-Saxon Christianity; the Church Father who secretly presides over it is his opponent Pelagius.

The logic of hell is nothing other than the logic of human free will, in so far as this is identical with freedom of choice. The theological argument runs as follows: ‘God whose being is love preserves our human freedom, for freedom is the condition of love. Although God’s love goes, and has gone, to the uttermost, plumbing the depth of hell, the possibility remains for each human being of a final rejection of God, and so of eternal life’. Does God’s love preserve our free will, or does it free our enslaved will which has become unfree though the power of sin? Does God love free men and women, or does he seek the men and women who have become lost. It is apparently not Augustine who is the father of Anglo-Saxon Christianity; the Church Father who secretly presides over it is his opponent Pelagius.

The first conclusion, it seems to me, is that it is inhumane, for there are not many people who can enjoy free will where their eternal fate in heaven or hell is concerned. What happens to the people who never had the choice, or never had the power to decide? The children who died early, the severely handicapped, the people suffering from geriatric diseases? Are they in heaven, in total non being, or somewhere between, in a limbo? What happens to the billions of people whom the gospel has never reached and who were never faced with the choice? What happens to God’s chosen people Israel, the Jews, who are unable to believe in Christ? Are all the adherents of other religions destined for annihilation? And not least: how firm must our own decision of faith be if it is to preserve us from total non being? Anyone who faces men and women with the choice of heaven or hell, does not merely expect too much of them. It leaves them in a state of uncertainty, because we cannot base the assurance of our salvation on the shaky ground of our own decisions. If we think about these questions, we have to come to the conclusion that in the end not many are going to be with God in heaven; most people are going to be in total non being. Or is the presupposition of this logic of hell perhaps an illusion the presupposition that it all depends on the human being’s free will?

If ultimately, after God’s final judgment on human decisions of will, all that is left is ‘heaven’ and ‘hell’, we still have to ask ourselves: what is going to happen to the earth, and all the earthly creatures, which the Creator after all found to be ‘very good’? If they too are to disappear into ‘total non being’, because they are no longer required, how can there then be a new earth’?

The logic of hell seems to me not merely inhumane but also extremely atheistic: here the human being in his freedom of choice is his own lord and god. His own will is his heaven or his hell. God is merely the accessory who puts that will into effect. If I decide for heaven, God must put me there; if I decide for hell, he has to leave me there. If God has to abide by our free decision, then we can do with him what we like. Is that ‘the love of God’? Free human beings forge their own happiness and are their own executioners. They do not just dispose over their lives here; they decide on their eternal destinies as well. So they have no need of any God at all. After a God has perhaps created us free as we are, he leaves us to our fate. Carried to this ultimate conclusion, the logic of hell is secular humanism, as Feuerbach, Marx and Nietzsche already perceived a long time ago.

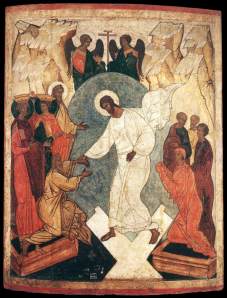

The Christian doctrine of hell is to be found in the gospel of Christ’s descent into hell, not in a modernisation of hell into total non being. Our century has produced more infernos than all the centuries before us: The gas ovens of Auschwitz and the atomizing of Hiroshima heralded an age of potential mass annihilation through ABC weapons. So many people have experienced hells! It is pointless to deny hell. It is a possibility that is constantly round about us and within us. In this situation, the gospel about Christ’s descent into hell is particularly relevant: Christ suffered the ‘inescapable remoteness from God’ and the ‘God forsakenness’ that knows no way out, so that he could bring God to the God forsaken. He comes ‘to seek that which is lost’. He suffered the torments of hell so that for us they are not hopeless and without escape. Christ brought hope to the place where according to Dante all who enter must ‘abandon hope’. ‘If I make my bed in hell thou art there’ (Ps 139:8). Through his sufferings Christ has destroyed hell. Hell is open: “Hell where is thy victory?’ (I Cor 15:55).

For Luther, hell is not a place in the next world, the underworld; it is an experience of God. For him, Christ’s descent into hell was his experience of God forsakenness from Gethsemane to Golgotha. In the crucified Christ we see what hell is, because through him it has been overcome. The true universalitv of God’s grace is not grounded in ‘secular humanism’. It is on that humanism, rather as the logic of free will shows that the double end is based: heaven hell, being non being. But the universality of God’s grace is grounded on the theology of the cross. This is the way it was presented by all the Christian theologians who were criticized for preaching ‘universal reconciliation’, most recently Karl Barth. In his ‘confession of hope’ the Swabian revivalist preacher Christoph Blumhardt (who profoundly influenced modern Protestant theology in Germany) put it this way: ‘There can be no question of God’s giving up anything or anyone in the whole world, either today or in all eternity. The end has to be: Behold, everything is God’s! Jesus comes as the one who has borne the sins of the world. Jesus can judge but not condemn. My desire is to have preached this as far as the deepest depths of hell, and I shall never be confounded.’

Judgment is not God’s last word. Judgment establishes in the world the divine righteousness on which the new creation is to be built. But God’s last word is ‘Behold, I make all things new’ (Rev 21:5). From this no one is excepted. Love is God’s compassion with the lost. Transforming grace is God’s punishment for sinners. It is not the right to choose that defines the reality of human freedom. It is the doing of the good.

http://www.plough.com/ebooks/ThyKingdomCome.html

Jason,

I first read the Blumhardt Reader by Vernard Eller in the spring of 1995. I was supposed to be doing other coursework, but couldn’t put it down.

-Greg

LikeLike

Here, Moltmann does what the best theology is supposed to do: in provocative prose, bring to the forefront the key theological issues at stake in what may seem at first to be a more narrowly focused controversy. At issue in the dispute about the doctrine of hell is nothing less than the relationship between humanity and God and the scope and nature of Christ’s Atonement. And endorsement of the doctrine of hell puts one, it seems to me, on the wrong side of both of these fundamental questions.

LikeLike

Hi, Jason,

I know it’s been awhile since you posted this but do you remember where you found this?

Spencer

LikeLiked by 1 person

…i think i just found it. Bauckham’s “The Eschatology of Jurgen Moltmann”?

LikeLike

Hi Spencer. It comes from Jürgen Moltmann, ‘The Logic of Hell’ in God Will Be All In All: The Eschatology of Jürgen Moltmann (ed. Richard Bauckham; Minneapolis: Fortress, 2001), 43–7.

LikeLike

Perfect! Thanks.

LikeLike